It’s a veritable race to the bottom as anti-abortion Republicans around the country leverage their control of state legislatures to enact the strictest possible limits on women’s reproductive rights. In a bizarre competition to pass the most stringent, plainly unconstitutional laws, North Dakota last week one-upped Arkansas, which just last week made national headlines by overriding the governor’s veto of a bill that banned abortion after 12 weeks, far earlier than the 23-24 weeks typically protected by Roe v. Wade. The Arkansas ban, which prohibits the procedure after a heartbeat is detectable by conventional ultrasound, has been blown out of the water by north Dakota’s six-week limit. That’s before many women even realize they’re pregnant, and the Guttmacher Institute estimates it would outlaw up to 75 percent of the state’s abortions.

Though the law does not say so in so many words, that it draws the line at the first sign of a heartbeat implies that transvaginal ultrasounds — the invasive procedure which sunk a Virginia bill in 2012 after drawing widespread mockery from late night talk shows and earning its own Doonesbury storyline – would have to be used. The Times notes that, though the Arkansas law was deliberately designed to avoid that morass, North Dakota’s effort may not:

One of the newly passed North Dakota bills outlaws abortions when a fetal heartbeat is “detectable” using “standard medical practice.” Heartbeats are often detectable at about 6 weeks, using an intrusive transvaginal ultrasound, or at about 10 to 12 weeks when using abdominal ultrasounds.

The bill does not specify a time threshold or whether doctors with a patient in the initial weeks of pregnancy must use the transvaginal probe. But some experts said that doctors in North Dakota, which has only one clinic performing abortions, in Fargo, could face prosecution if they did not use the vaginal ultrasound when necessary to detect a heartbeat. Doctors who knowingly perform abortions in violation of the measure, if it is adopted, could be charged with a felony that carries a five-year prison sentence; the patients would not face criminal charges.

Well, gee, that’s generous. Women can be forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term, with no more rights than a farm animal, but North Dakota at least draws the line at throwing them in jail.

The bill headed to the governor’s desk was not even the farthest-reaching proposal on the table. Another bill would have outlawed abortion altogether, and still in the works is an amendment to the state constitution declaring that life begins at conception. If approved by the House, voters would weigh in on the amendment — and potentially commit the state to spending taxpayer dollars to defend it against the inevitable legal challenges — in November 2014. State Rep. Bette Grande, who sponsored the bill, tells Politico that “I dispel the notion that this bill should be defeated because of litigation costs.” Leaving aside the fact that Grande can dispute the notion but hardly dispel it in the eyes of those who don’t want their taxes wasted on a futile court battle, I would imagine that many women in North Dakota would disagree.

The Arkansas law is already being challenged in court, and even the ten states that ban abortion at 20 weeks face high legal hurdles. Idaho’s 20-week ban, which was predicated on the scientifically dubious theory that the fetus can feel pain at that point, was recently struck down by a federal judge who bitingly criticized the the law as unconstitutional, citing legislators’ “clear disregard of this controlling Supreme Court precedent and its apparent determination to define viability in a manner specifically and repeatedly condemned by the Supreme Court.” If such “fetal pain” laws can’t survive a challenge, the prospects are dim for North Dakota’s earlier “fetal heartbeat” limit. There’s little question that the laws, which blatantly contradict Roe, will be overturned. The ant-abortion activists and legislators who pushed the ban know this full well — but they don’t care. It’s all part of their strategy, a strategy that represents a major shift among activists previously content to chip away at legalized abortion piece by piece. “It’s as though legislatures all across the country are saying, ‘We don’t really care. We’re just going to do it anyway in the face of the Constitution,” says the lawyer who successfully challenged the Idaho ban. (He brought the suit on behalf of the woman whom the state had the audacity to charge with a felony for obtaining an illegal abortion. Classy, Idaho.)

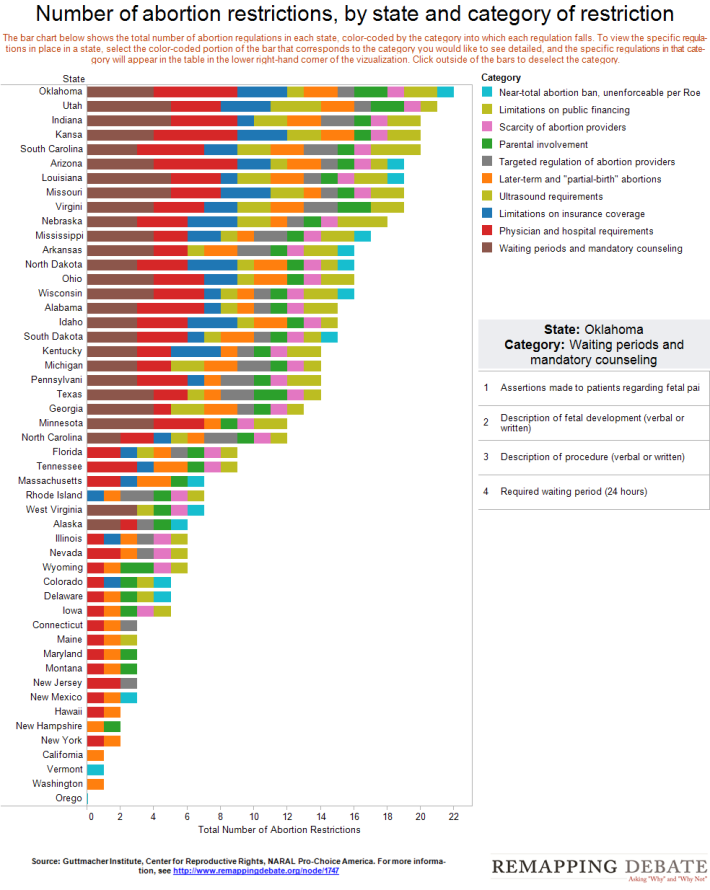

The North Dakota legislation is part of a nationwide crackdown on abortion that the Guttmacher Institute estimates resulted in an unprecedented 92 number of state- level restrictions in 2011 and 43 more in 2012. Most of these restrictions follow the playbook that has guided the anti-abortion movement for the past generation; instead of seeking the pipe dream of a complete reversal of Roe, they have sought to erode its foundations, to pass laws that eat away at its edges and make it harder and harder for women to obtain a procedure that, in states like Mississippi, remain legal in name only. So called TRAP laws (for “Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers”) saddle clinics with such capricious, onerous rules — everything from the width of hallways to the size of the waiting room is prescribed in exacting detail — that they are effectively pushed out of business. Requirements that doctors obtain admitting privileges at local hospitals hostile to abortion and bans on tele-medicine prescriptions of chemical abortions or the morning-after pill make life as hard as possible for organizations like Planned Parenthood, which also takes financial hits from state and federal lawmakers seeking to bar it from government programs and restrict its access to Medicaid and women’s health dollars. Never mind that federal law already mandates that such funds go not to abortion but to Pap smears and STD tests; for conservatives, the only good Planned Parenthood clinic is a shuttered one. When they’re not attacking access to abortion, opponents are restricting the rights of women themselves, imposing multi-day waiting periods, requiring parental notification for minors, and forcing women seeking an abortion to listen to a lecture from a crisis pregnancy center that peddles false information about links to breast cancer and informs her that killing her baby will send her straight to Hell.

As ridiculous and radical as these laws are, they are promulgated by a relatively pragmatic faction of the anti-abortion movement. Knowing that the chance of the Supreme Court overturning Roe is slim and concerned that challenging the ruling directly might backfire, producing the sort of reaffirmation of abortion rights that the Court handed down in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, opponents have settled for dramatically curtailing, not ending, a woman’s right to choose. The folks behind north Dakota’s law have no such compunction. Frustrated with incremental progress, they have abandoned caution for brazen challenges like six-week bans, preferring instead to launch a frontal attack on Roe, consequences be damned. This new front in the reproductive wars include groups like the Family Research Council and the Susan B. Anthony List, which stood by Todd Akin after his controversial comments about “legitimate rape” rarely resulting in pregnancy. “They don’t see him as a politician who has made a career ending gaffe,” Sarah Kliff of Wonkblog wrote at the time. “In their view, he’s a strong abortion right opponent who articulated a tenet of the pro-life movement: Abortion should be illegal in all situations, rape included.”

Of course, prohibiting abortion in cases of rape and incest is wildly unpopular with the American public; 75 percent feel that it should always be legal in such situations, far outpacing the number who believe abortion is permissible under any circumstances. The extremist wing of the anti-abortion movement is gaining steam; in many cases, it’s endorsed by politicians like Paul Ryan regarded as extreme only on the budget, not social issues. Ryan was a prominent co-sponsor of the Sanctity of Life Act, a “personhood” bill that defined life as beginning at conception and that would have outlawed abortion altogether. Even the official platform of the Republican party has repeatedly bowed to the strain of radicalism evident in North Dakota, endorsing the idea that “the unborn child has a fundamental individual right to life which cannot be infringed” in any circumstances, rape or incest included. (The state bill likewise eschews those exceptions, permitting abortion only in cases that threaten the mother’s life or “irreversible impairment.”) By claiming that “the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections apply to unborn children,” the GOP officially granted “life and liberty” to embryos — a step even North Dakota’s legislators were unwilling to take. At the time of the Akin controversy, Kliff detailed the unpopularity of personhood measures, which were rejected by comfortable margins in Missippi and Colorado, largely on the premise that they would never pass muster with the courts:

That’s left the pro-life movement choosing between the lesser of two evils: Supporting abortion bans that do not have a shot at becoming law, or standing behind imperfect restrictions with fewer political liabilities.

With today’s news from North Dakota, it’s clear which direction the movement has chosen. Six weeks is only the beginning, however; Bette Grande, the state representative who sponsored the law, makes it clear that it was engineered to directly challenge Roe. As the Times reports:

“A heartbeat is accepted by everyone as a sign of life,” she said in a blog posting on Tuesday as she argued that it was time for the Supreme Court to revisit the definition of viability.

In light of the North Dakota bill, Sarah Kliff takes another look at the state of anti-abortion activism, contrasting the incrementalists with the all-or-nothing crusaders:

The other faction tends to be more aggressive; they don’t accept the Roe v. Wade decision as law and don’t use it as a framework for passing legislation. They tend to be more ideological and less pragmatic, thinking about the best ways to restrict abortion regardless of whether they’ll be upheld by the Supreme Court.

The more aggressive wing of the antiabortion movement up until now, has had difficulty gaining traction with it’s “all-or-nothing” approach. A slew of proposed bills to declare life as beginning at conception all failed, most notably in deep red Mississippi. In 2013, however, they appear to be taking hold. Arkansas and North Dakota have passed abortion restrictions that skew more toward the ideas of those who want to eschew Roe altogether, even if those laws are likely to get struck down in court.

The split to some degree mirrors the divide in any movement for social change; even civil rights advocates were divided between incrementalists who thought it better to push for slow changes and more radical members like Malcom X who demanded immediate, total equality. Anti-death penalty activists are similarly torn, with one group playing on public sympathy for the wrongly convicted and mentally ill, and another that refuses to acknowledge that eye-for-an-eye justice is ever appropriate for anyone, even the most odious of killers. It’s pragmatism versus principle, and sometimes it’s results versus ideals. Even pro-choice advocates have a similar split, with some forces encouraging the debate to be framed as one over a woman’s fundamental freedom of reproductive choice and others rooting their appeals in sympathetic cases of rape and incest that even many anti-choicers agree should make women “worthy” of abortion. The civil rights movement had more success in pushing for hard for a complete end to “separate but equal”; it bet on the strength of its convictions, that racism in any form was wrong and not to be accommodated.

Anti-death penalty absolutists and gun control advocates have been less successful. On gun control, despite a seeming upswell in the number of Americans willing to consider stricter regulations, the incrementalists have won out. The assault-weapons ban is dead in the Senate, which — depending on your point of view — represents either lawmakers’ predictable capitulation to the NRA or a pragmatic pulling back from a “reach” measure that even the Brady Center conceded was unlikely to pass in the first place. Perhaps this is no big deal; after all, the previous ban was so full of holes (unlike its draconian North Dakota abortion-rights counterpart) that it was difficult even for proponents to find evidence that it made much of a difference. Easier-to-pass bills expanding background checks and cracking down on straw purchases may do more to curb gun violence, but they also lack the moral victory of an assault weapons ban. Were gun control advocates as unhindered by political and legal reality as abortion opponents, they would have waged an all-out crusade for the ban, consequences — it could, for example, have taken the less controversial measures down with it — be damned. But as the Times quotes Jon S. Vernick of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research as saying, the ban “made it harder to reassure some folks that advocates of gun-violence prevention measures were not trying to take away anyone’s guns, but simply trying to make it harder for high-risk people to acquire guns.” That is the epitome of the pragmatic, incrementalist philosophy.

The legislators in North Dakota have the advantage of a split in their movement; even when the six-week ban is struck down by the courts, the efforts of the incrementalists to erode abortion rights via waiting periods and TRAP laws will persist. Either way, the movement notches a win. By contrast, gun control advocates decided they could not afford to fight on two fronts at once, as the assault weapons ban realistically would be paired in the Senate with the less extreme measures. The defeat of one could poison the well for the others — the Republican rejection of even the extremely popular step of universal background checks as a supposed “precursor to a national gun registry” that is actually prohibited by federal law shows just how touchy gun control issues are — unlike the North Dakota ban, which seems unlikely to dissuade the more traditional wing of the pro-life movement from continuing to advance inch-by-inch legislation. On a state level, however, opponents or abortion and guns share more similarities than differences. The federal “personhood” bills sponsored by Paul Ryan and Todd Akin are doomed, but at the state level, conservative legislatures are far more conducive to defining embryos as people and mandating transvaginal ultrasounds. Likewise, though the gun control movement is weak on a national scale, it has had more success in deep blue states like New York and Illinois, where Democratic governors are far more open to the assault-weapons bans and restrictions on magazine size that make U.S. senators and representatives nervous.

Likewise, the movement to abolish capital punishment is torn between accepting halfway victories and pushing for the whole enchilada. And like the anti-abortion movement, it plays on public sympathies for the most media-friendly examples of their cause. If more states have moved to repeal capital punishment, as Maryland recently did, it is not because the American public agrees that murdering murderers is wrong but because, as Ezra Klein writes, “the media has won the death penalty debate.” Coverage of DNA exonerations and criminals hemmed in by violence and broken families, not any great moral shift, has made the public skittish about executions. Those who insist that the death penalty is wrong because of its moral implications for the executioners — vengeance is not a legitimate reason for such severe punishment — are not winning based on their unbending demands for abolition, just as pro-abortion activists will never win their case based on the idea that reproductive choice is a fundamental right. (Interestingly, I am an absolutist on both issues: the death penalty is wrong full stop, any specious comparison to “killing innocent babies” notwithstanding, and abridging a woman’s rights is wrong full stop.) Likewise, the anti-abortion movement has thus far had more success in chipping away at Roe gradually through waiting periods and regulations. Is it poised to have the wider, more monumental success that anti-death penalty advocates have been denied?

If so, it may be because the absolutists behind North Dakota’s ban have paired their efforts with incrementalist strategy by finding a way to simultaneously appeal to conventional sympathies. Just as the average person is horrified at the idea of executing a mentally challenged perpetrator who understands so little of his situation that he asks to save the dessert of his last meal “for later,” the average person recoils at two specific motivations for abortion: sex selection and genetic “weeding out.” The former draws more distaste than the latter, but both are issues that make the public queasy and win emotional support for pro-lifers, who can easily conflate the termination of a female or genetically flawed embryo with the killing of a female or disabled individual.

Thus, beyond the viability standard, the North Dakota bill pushes the envelope in other ways as well. It would make the state one of four to ban sex-selective abortion, on the supposition that parents eager to have a boy are discriminating against female embryos, and the first to prohibit abortions based on genetic abnormalities like Down syndrome. More than the debate over viability, which is fairly clearly defined under Roe and is an issue on which conservatives attempting to mandate transvaginal ultrasounds have been ridiculed by the public, these two restrictions present thorny questions for abortion-rights absolutists. It’s easy to caution against a slippery slope — once doctors start demanding that women explain the reason for an abortion, how long will it be before cases of failed birth control and simple personal preference are declared unworthy? — and indeed, the director of the ACLU’s Reproductive Freedom Project released a statement condemning laws that seek to substitute the judgment of politicians for the personal choices that must be made by a woman and her doctor:

We urge the governor to veto all of these bills to ensure that this personal and private decision can be made by a woman and her family, not politicians sitting in the Capitol.

That’s true, as far as it goes; there is no justification for telling a woman that she must have a good reason to exercise her constitutional rights. Imagine what the Second Amendment crowd would say if a deep-blue state like New York attempted to pass European-style laws that require those purchasing a firearm to prove they need it for self-defense. There should be no qualifications of a right as fundamental as a woman’s ability to control her own reproductive system. But bans on things like gender discrimination that most of the population finds distasteful and from which people automatically recoil — after all, isn’t it just a step from aborting a female fetus to actual female infanticide? — tend to put organizations like Planned Parenthood on the losing side of public opinion. Yet if you believe, as I do, that the right to abortion rests on a woman’s autonomy and that the reason for her decision should never be anyone’s business but her own, you are forced into the uncomfortable position of seeming to approve of sex-selective abortion. Given that I’m such an unabashed feminist that I roll my eyes at anyone cowardly enough to shrink from the label (feminism is the radical notion that women are people, too) and think the word “Mrs.” should go the way of corsets and poodle skirts, it’s a quandary that seems important to consider.

My own conclusion? It’s possible to frown on the morality of prizing boys above girls without feeling that such morality is something that should be legislated. People make decisions of which I do not approve all the time — they cheat on spouses, betray friends, et cetera — that nevertheless should not be illegal. What makes me uncomfortable about sex-selective abortion is not that I think it kills a baby girl — if an embryo is not the equivalent of a person, the harsh truth is that a female embryo is not a girl — but that it says something disturbing about the parents who make such a decision and the society that encourages it. I disapprove of the mindset that one gender is better than another, but discrimination is only illegal if it hurts a person — and I don’t think a fetus is a person. Conservatives have the easier argument to make here, as it is easy to conflate aborting a female fetus with killing a female baby, but giving into such logic begs the question and unwittingly adopts the anti-abortion framing device of fetuses as people. Choosing abortion simply because the gender of the fetus isn’t “right” is not a choice I would make or even one that I think is ethical, but it is one that every woman must decide for herself. It is certainly not one that should be policed by elected officials attempting to divine the motivation of every woman that turns up at a Planned Parenthood clinic. How, exactly, would we know when an abortion was prompted by dissatisfaction with the sex of the potential child? Would couples be forced to wait until the delivery room to learn the gender of their offspring? Procedures that reveal the fetus’s gender could always be banned — oh, but then what would happen to the ultrasounds mandated by the law itself? Perhaps we could draft Stasi-like government agents to show up on couples’ doorsteps to inspect the color scheme of the nursery. Blue, when the child you’re carrying suggests pink? No abortion for you!

Such a ban also constitutes a solution without a problem. There is no evidence that sex-selective abortion is rampant in the U.S., certainly not to the degree that it is in places like China, where the preference for boys over girls has created an imbalance in the gender ratio that now stands at number. Conservatives often present the situation in China as a grim harbinger of what will happen in America without bans like the ones passed in North Dakota, and though this is an effective tactic for winning public sympathy, it simply doesn’t comport with reality. The problems in China are real; what was once a personal decision has, when combined with the practice of female infanticide that should obviously be as illegal as any other type of murder, produced dangerously skewed gender ratios that undermine the stability of society and present a demographic problem for a society whose birthrate is already slowing. Only if the United States shared such problems could I conceivably consider regulating sex-selective abortion. Constitutional rights have long been subject to limits based on the public good; speech that incites violence or constitutes obscenity is not protected by the first amendment, the right to bear arms does not confer the right to bear any arms in any situation (think machine guns and permit requirements), and even abortion is limited to the first 24 weeks of a pregnancy, before the state is thought to have a legitimate interest in the survival of the fetus. If America truly were descending into a womanless post-apocalyptic hell, perhaps such legislation would be warranted — and even then I would find the argument a tough one to accept. You just can’t criminalize a moral decision that doesn’t hurt an individual or society at large.

Anti-abortionists would argue that even moral decisions can hurt society; this is the same logic they use to argue against gay marriage, claiming that the government has an interest in promoting stable families and traditional values. Needless to say, I would disagree. Sure, the state has an interest in, say, promoting public health, as it foots the medical bills of those who go without insurance. But the state has no inherent interest in favoring one value system over another. While we can all agree on values like murder is wrong, when we disagree on what defines murder, conservatives should not be allowed to substitute their definition for the law as interpreted by the Supreme Court. “Public interest” is often hard to define; both conservatives and liberals can be hypocritical when they push their respective visions of how the state should intervene to encourage a better society. It’s a hard line to draw, and one that relies on often tenuous connections between morality and its real-world effects. A study comes out demonstrating that delaying marriage hurts the economic prospects of young people: Is this a problem government policy should seek to remedy or not? Is it like soda regulation (a public health problem) or more akin to abortion, a moral question that liberals firmly believe should be off-limits to “nudging” by the state? Even if a policy can produce beneficial outcomes — stronger marriages, more children — how far should we go in legislating morality? Are liberals hypocrites — am I a hypocrite — for embracing regulation on small matters like plastic bags and nutritional labeling while at the same time rejecting similar rules designed to shape society? Why do I accept that government policy should seek to remedy, say, poverty, while bristling when conservatives propose remedies (tax breaks for married couples, etc.) that infringe on what I see as as sacrosanct: a woman’s ability to make her own decisions, whether on marriage or childbearing? Of course, conservative policy prescriptions might be easier to stomach if they truly supported ones that tackled real-world problems — health care and child care for women who do choose to carry their pregnancies to term — rather than simply dictating right and wrong without regard to the future of the children they would force women to bear.

If there’s any issue surrounding abortion more fraught than gender, its disability. Couples who end a pregnancy based on a predilection for blue or pink may be rare, but research shows that the vast majority of women who learn that their fetus carries the genes for Down Syndrome choose to terminate. Prenatal testing has become so routine and common that women are regularly informed when their potential child carries a genetic defect. Is it wrong to end such pregnancies? Those who argue that doing do discriminates against those with disabilities again conflate fetuses with people; it may sound horrible to say that a disabled baby is “unwanted,” but I suspect that a couple presented with an actual baby would want it as much as any other. An embryo, however, is not a baby, and having an abortion is not the same as killing your child. Of course, conservatives would disagree — the personhood of a fetus is the crux of the abortion debate in general, and that the logic used to argue against genetics-based abortion is identical to that used to argue against the procedure overall indicates to me that, as cold as this sounds, there is nothing unique about disability-related abortion (beyond its emotional valence) that should precipitate a law that treats it any differently from any other abortion. Conservatives would say that declining to carry to term a “flawed” pregnancy devalues life, that it makes a judgment about whose life is worthwhile and whose is not, but you could just as easily make the opposite case: perhaps parents who choose not to have a disabled child are in fact more sensitive to the value of life, in that they do not want to impose one filled with suffering — and we can argue until the cows come home about what degree of disability causes suffering — on their future child. The morality of “weeding out” individuals we regard as defective, especially when many of those labeled as such can lead happy and fulfilling lives, is tricky. How far would we go to ensure that our children are “perfect,” and where to we draw the line between disability and preference? Though a Gattaca-like world is indeed dystopic, I think many prospective parents would take exception to the idea that choosing only a healthy pregnancy is the same as choosing one in which the fetus has blue eyes or athletic ability.

These are difficult issues; if I were faced with such a pregnancy, I don’t know what decision I would make. But I know that its a decision that should be mine and mine alone to make, not one that should be outsourced to politicians whose ideas of morality may be starkly different from my own. Ironically, the very women ensnared by the North Dakota ban are those least likely to be the careless, loose women demonized by the GOP as using abortion as birth control or failing to take responsibility for premarital sex. The women who will be hit by this law are those who genuinely want to have a child, who are making an agonizing decision to end a pregnancy that they otherwise would happily carry to term. They want to be mothers, and are most likely to share the conservative morality that emphasizes the family and champions child raising. Yet these are the women that lawmakers in North Dakota would seek to dictate to.

There’s also the not-insubstantial matter of how to police abortions based on disability or gender; would anyone undergoing a prenatal test be prohibited from having an abortion, on the off chance that she would be acting based on the results? How would lawmakers distinguish between a woman whose prenatal year revealed a disability who would have sought an abortion anyway and one who was seeking to end a Down syndrome pregnancy? Until doctors can read minds, there is no way of differentiating between the two cases. Simply banning any abortion of a fetus discovered to have a genetic abnormality would not only ensnare women desiring an abortion for myriad other personal or health reasons but would have the perverse incentive of discouraging the very prenatal testing that can lead to in utero treatments or prepare parents for a disabled child. Other logistical problems abound; if sex-selective abortion is banned, what about in vitro fertilization techniques that are also able to determine gender? Surely some conservatives would be content to ban anything that tampered with an embryo (or even an egg), but most Americans would likely find that as radical as transvaginal probes. For abortion rights advocates who reject the idea of fetal personhood, this should only reassure them of their stance. If an embryo in the womb is no different than an embryo in a Petri dish and discarding the latter is permissible, it follows logically that the former should not be accorded special protection. We may look with distaste on couples undergoing fertility treatment who select embryos based on gender, but there seems to be less appetite for regulating this practice than regulating sex-selective abortion. It simply doesn’t present as compelling an emotional appeal.

It’s no surprise that the anodyne statement issued by Planned Parenthood in response to the six-week ban spoke of politicians who demonstrate “disregard for a woman’s personal medical decision-making” makes no reference to the particulars of the bill. The organization knows it is not going to win a messaging battle with the Frank Luntz spinmasters of the right, the same people who have so successfully turned abortion from an absolute, non-negotiable right into a tragedy that even liberals are forced to concede should be “safe, legal and rare.” Of course, no one relishes an abortion, and it can indeed be a wrenching decision, but the word “tragedy” plays into the conservative framing that equates the procedure to the murder of a baby. Likewise, equating sex-selective abortion with the murder of baby girls is a relatively easy leap for opponents, and even advocates like Planned Parenthood seem reluctant to challenge anti abortion forces on the fundamentals of the issue. Perhaps this is unsurprising, given that the organization recently backed away from the phrase “pro- choice,” reasoning that thinking of abortion as an easily-made choice and not an unfortunate necessity lacks appeal to a generation of women wooed by pro-lifers and exposed to bloody poster-sized photos of dismembered fetuses. Perhaps Planned Parenthood is just being pragmatic, but such pragmatism speaks to its underdog status. The law may currently be on the side of abortion rights, but the enthusiasm and audacity are on the side of the activists in North Dakota bold enough — and apparently confident enough in an eventual victory before a Supreme Court that has shifted dramatically to the right — to pass a law that is so obviously and intentionally unconstitutional.

Even beyond touchy issues like sex-selective abortion, the pro-choice movement doesn’t always do much to help itself in the court of public opinion. There are a few bad apples in every profession, and like the scheming Lehman bankers who gave Wall Street a bad name, abortion practitioners like Philadelphia physician Kermit Gosnell don’t do anything to endear the movement to a public generally skeptical of what conservatives have labeled “abortion on demand.” Gosnell is currently on trial for performing illegal late term abortions after the 24-week pre-viability window and is accused of operating under unsanitary conditions that may have led to the death of a patient. The doctor is defending himself, arguing that the fetuses could not have survived outside the womb and alleging that the case is a racially “prosecutorial lynching,” but he does seem to have ignored dangers to vulnerable women, and the trial undoubtedly gives the abortion-rights movement a black eye. Even staunch advocates aren’t pressing for the right to abortion until two seconds before delivery — I don’t pretend to know when a fetus “becomes human,” as conservatives might say, but there is a point at which survival outside the womb is so likely that the abortion, unless performed to save the mother’s life, crosses the line — but it does play into the right-wing accusation that liberals support “infanticide” because, like the president, they oppose restrictions that undermine Roe with dramatic talk about saving “babies” that “survive botched abortions.” However, it is indeed legitimate for pro-choicers to ask ourselves why, if we don’t believe that fetuses are babies, we nevertheless recoil at cases like that of Dr. Gosnell. Does such a reaction make us hypocrites, or just not as certain as the right-wingers convinced of the evils of abortion that we know when life begins and when a woman’s right to choose is superseded by the understandable (if not entirely logically consistent) unease over late-term abortion? In one respect, pro-choicers like myself seek to define the debate in black and white — abortion is permissible because fetuses are not people, end of story — while in other respects we acknowledge that, yes, there are shades of gray. Just because we don’t see a six-week-old embryo as worthy of protection does not mean we feel the same about what is essentially a premature birth. We argue that deference to a woman’s autonomy requires us to consider whether she wants a pregnancy or not, and our language defers to this reality (we speak of fetuses at NARAL rallies but readily talk of “the baby” and “your child” when we attend friends’ baby showers), but even we are reluctant to defend someone like Gosnell, especially given his apparent disregard for the safety of his female patients.

It’s easy — and, in my eyes, necessary — to condemn the North Dakota ban. But such infringements on freedom raise complicated questions that the pro-choice movement would do well to at least consider, if only for the purpose of working through its own positions and asking itself how far it will push its principles. If we’re not entirely comfortable with some of the conclusions we come to, that’s something to think about. There’s something to be said for thinking, and if Aristotle is correct that the unexamined life is not worth living, such discomfort or cognitive dissonance is a small price to pay for a little examination.