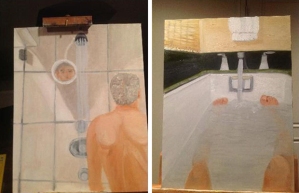

The most bizarre thing to emerge from the hack of of several Bush family members’ e-mail accounts is not W.’s paintings but the subsequent “critical” reaction. I include the scare quotes because I’m not entirely certain whether some of the supposed analysis of the two bathroom self-portraits — one of the former president in the shower and another of himself reclining in the tub — is serious or tongue-in-cheek. Roberta Smith, an art critic for the Times, calls him a “serious amateur,” though it’s unclear whether that means better than an amateur or a complete amateur. After some standard art-speak about the stylistic awkwardness, Smith writes:

The two paintings could be said to depict the introverted self-absorption for which Mr. Bush is known. Perhaps, he is trying to cleanse himself in a more metaphorical way, seeking a kind of redemption from his less fortuitous decisions as president.

Really? Smith’s blog post is a mix of humor — Bush is “a heck of a lot better than any number of world leaders whose names spring to mind, foremost Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler” — and genuine evaluation — “These works make you wonder if Bush is familiar with Jasper Johns’s “Seasons” — so the psychoanalysis could be intended either seriously or as parody.

At The New Republic, Michael Schaffer actually labels his piece “A Freudian Analysis,” and it’s pretty much what you’d expect from the id-obsessed psychoanalyst. On the shower painting, he muses:

Though superficially an image of an everyday activity, the painting also points to an inner turmoil over one of the biggest calamities of the Bush administration: Hurricane Katrina . . . .That Bush would allude to Katrina in a painting ostensibly depicting an act of self-cleansing most likely speaks to his guilt over his handling of the storm.

In the bathtub picture, Schaffer also sees “an allusion to more ignominious things.” The man reclining beneath the stream of water in this case indicates “subconscious remorse about waterboarding.” He sees the towel hanging above the faucet as “a representation of the interrogator himself, preparing to give the helpless captive a dunk in the water even as the prisoner tries to distance himself.”

Again, parody or not? Schaffer’s analysis is legitimate, as far as Freudian assumptions go, but does he honestly think torture and Katrina are the driving forces behind Bush’s artwork? It’s hard to tell.

Philip Kennicott, a style writer at the Washington Post, defends the Peeping Tom imuplse, writing that “there’s no way that we can’t look through the window they seem to offer us into the psychology of someone who was once the most powerful man in the world.” Kennicott is mostly respectful, however, admitting that “neither painting is polished, yet both have some merit.” He can’t resist weighing in on the message behind the paintings, though he couches his analysis in a some people say construction:

It won’t be long until someone offers a partisan reading of the paintings, which might follow these lines: Both are about bathing, which may suggest some sense of guilt, like Lady Macbeth’s frantic hand washing in the Shakespeare play (“out damn spot…”). After eight years as supreme commander, making decisions in a time of war, perhaps Bush feels a need for some kind of spiritual or mental cleansing.

Well, Kennicott is right about one thing: partisan reading abound. In an e-mail to Slate, Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight actually writes, “Is George W. finally coming clean? Out, damned spot! Out, I say!” Meanwhile, the muckraking right-wing Washington Free Beacon headlined its coverage “Greatest Living President is Also a Fantastic Artist.” (A Beacon staffer later professed this to be “a joke,” but one suspects that, though “fantastic artist” may have been a joke, the “greatest living president” part was not.)

At the urban pop culture guide Blackbook, Miles Klee is harsh in his assessment of Bush’s legacy:

If you ask me there is something of a simple allegory to the moments chosen here: the discredited former leader trying to wash himself clean of the long failure that was his life

New York Magazine blogger Dan Amira, who is decidedly not an art critic, sees “soul-searching introspection” in the paintings, then lards on the melodrama:

Bush, slightly hunched, is standing out of the water, staring off into the corner of the shower, as if contemplating past sins that can never be washed away, no matter how much soap you use and how hard you scrub. His disembodied face appears in the shaving mirror, looking back at Bush through an impossible angle, like a haunting apparition. You can’t hide from yourself, the face is saying. You can’t hide from God.

Yikes.

By no means am I of the art-critic school that says a flower is just a flower, a position that seems untenable given how many artists are on record testifying that their flowers are really symbols for — take your pick — vaginas, youth, or the impermanence of beauty. Especially in the modern era, when artists choose their subject and medium instead of churning out altarpieces for the local branch of the Medici family, almost all art has meaning, whether direct (a friend’s soul revealed through a portrait) or more abstract (color field as a religious metaphor). Even Vladimir Malevich’s seemingly straightforward squares were deeply rooted in the philosophy of Suprematism. And I have no problem with evaluating art through the artist’s life and experience. Artist’s statements are often so personal — Louise Burgeois’s childhood trauma infuses all her work, especially the latex and wood “Destruction of the Father,” and the video art of David Wojnarowicz embodies the pain of the AIDS epidemic — that there’s no other way to take it. Francis Bacon couldn’t have been a totally happy guy.

Sometimes, however, Freudian psychobabble goes too far, especially when applied to people who may paint not to express angst but because they enjoy the act or find it relaxing. You don’t have to be Van Gogh to have a message in your work — amateur artists have emotions to express just like professionals, and often the difference is less in skill than in the audacity necessary to convince a gallery a piece is worth more than ten bucks — but it is important to remember the distinction between art and craft. I like to draw and collage, but not because I want to communicate a deeper meaning; I enjoy it, in the same way I enjoy baking bread. The fact that it’s a hobby doesn’t make it meaningless, of course; I used to write stories as a hobby, and you’d have to be pretty dense not to see some meaning in the repeated trope of young people leaving home. But often meaning, for people who craft, is not as deep as a colonoscopic examination of personal failings or childhood trauma. I once took an art class from a woman who painted cats — not, I’m fairly sure, as a way to express repressed female sexuality but because she really liked cats.

Similarly, do we have any evidence that Bush was more than a Sunday painter, choosing his subjects based on what was in front of him and what he found interesting? In a 2012 profile of Jeb Bush, New York Magazine’s Joe Hagan quotes an acquaintance as saying Bush had “become increasingly agoraphobic” (though I doubt he meant confined to the bathroom). If the post-White House Bush is indeed a homebody, painting “portraits of dogs and arid Texas landscapes,” is it any surprise he has chosen easily accessible, close-to-home subject matter? The Post’s Philip Kennicott concurs with this Occam’s Razor interpretation:

People who are constantly in the public eye, who live with cameras tracking their every move and recording their every word, find privacy only in the bath. It is where they think, unwind, and enjoy the rarest of luxuries: Alone time. If painting is a form of private relaxation, it’s not surprising that Bush would turn to himself in his most secluded sanctum as a subject.

Sometimes the simplest explanation is the best. Gentle introspection is not as far a leap as residual angst over Guantanamo. It’s also consistent with the fact that, apart from a painting of his dog Barney that he chose to make public, Bush has kept his artwork mainly to himself (and, as he must now be regretting, his sister’s inbox). Other celebrities paint art with subtle meaning, but that ignores the reality that they’ve all chosen to show. By entering the message-laden modern art world, in which every streak of paint purports to telegraph grave significance, they have conceded that their work harbors a deeper point. Bush, on the other hand, is private, like most hobbyists. Perhaps the classiest response from the art world came from a Baltimore museum that told the Huffington Post it “cannot responsibly comment on this subject as art, as it was not President Bush’s public submission, but a breach of his private communications which is equal to theft.” Unlike Bob Dylan, whom Roberta Smith name-checks in her post on Bush, or James Franco, I doubt he’ll be issuing an artist statement or creative manifesto anytime soon.

It’s conceivable there are psychological undercurrents to the water — hey, Bush is famously born-again, so maybe it symbolizes baptism and renewal after a grueling eight years — but you don’t have to push it as far as seeing a waterboarding gag in an innocent bath towel. Liberal critics may assume he feels guilty about torture, but do we know he even considers it anything but an “enhanced interrogation technique”? He never expressed remorse while in office, so why would he start now? Certainty, about weapons of mass destruction to whether foreign countries were “with us or against us,” was always a hallmark of the Bush administration. I somehow doubt a few waterboarded terrorists haunt his thoughts enough to compel him to paint himself in their place. Bush strikes me, if I may engage in my own psychoanalysis, as someone who would rather pray away the guilt than paint it. Where does the overreach end? If Obama, in his retirement, gets his pilot’s license and tools around the country in a Cessna, does that means he’s channeling guilt about drone strikes?

Some of the critical interpretations are more straightforward and believable: naked bodies pretty clearly speak to concerns about the body and its fragility in old age. (Indeed, the hacked e-mails contained poignant discussion of George H.W. Bush’s failing health, including talk of preparing a eulogy.) Clare Malone of the American Prospect weighs in:

The vanity of an older man who has maintained a lanky frame is there—he paints his naked torso, finely shadowing those 66 year old back muscles with pride, still taut from years of brush-clearing and bill signing.

This rings far truer than the rest of Malone’s take, which concludes “he can’t seem to look at himself in the mirror. Nor can he escape himself it seems—the mirror’s reflection is relentless, inescapable.” It’s tempting to over-analyze. You start down one path, assuming that X stands for Y, and before you know it you’re jumping feet-first down the Guantanamo-guilt rabbit hole. One assumption leads to another; it could go on forever. That’s why I like Jerry Saltz’s succinct and refreshingly sympathetic take in New York Magazine. Saltz, one of my favorite art critics, is surprised to discover he finds Bush “a good painter.” In reply to a commenter, he says “I DO like them but without air-quoates [sic]or irony. I actually like ’em.”

Though Saltz traffics in depth-probing, writing that “Both border on the visionary, the absurd, the perverse, the frat boy,” he also offers a frank evaluation — a testament, perhaps, to his day job reviewing some of the city’s wackiest You call that art? exhibitions. He continues: “Each echoes the same isolation in small space. Rumination without guilt. Thought without dark nights.” But Saltz pays more attention to the actual art than the attending psychodrama, and in doing so produces a genuinely honest analysis worth quoting at length:

I love these two bather paintings. They are “simple” and “awkward,” but in wonderful, unself-conscious, intense ways. They show someone doing the best he can with almost no natural gifts — except the desire to do this. The reclusion and seclusiveness of the pictures evoke the quietude (though not the insight, quality, or genius) of certain Chardin still lifes. These are pictures of someone dissembling without knowing it, unprotected and on display, but split between the promptings of his own inner drives and limited by his abilities. They reflect the pleasures of disinterestedness. A floater. Inert. The images of a man who saw the entire world from the inside but who finds the smallest, most private place in a private home to imagine his universe.

Saltz, a longtime champion of expanding art to the masses, writes encouragingly, “Paint, George, paint. Paint more. Please. If you exhibit it, I’ll write about it. The Whitney Museum of American Art should get on the stick and offer this American a small show.” That final remark raises an interesting point about outsider art; if Bush is no better than rest, why is one mocked and the other in galleries? As Smith writes in the Times,

For many these works might qualify as outsider art; they give every indication of having been made by a self-taught artist. But so do many paintings shown in the insider art world of today.

Smith imagines the artists that might hang alongside “Bush Bathing” and “Bush Showering.”

And one can imagine them being not too out of place in a group show that might include the figurative work of Dana Schutz, Karen Kilimnik, Alice Neel, Christoph Ruckhaberle and Sarah McEneaney.

Yet no one is taking Bush’s work seriously, as work by someone like Neel would be taken. Smith’s commentary is particularly interesting given the attention paid recently in the Times to the Outsider Art Fair, which showcases work that the average person would not consider any more “skilled” than Bush’s. Smith called the event “a wonderfully eccentric jewel in the crown of New York art fairs,” a far more glowing review than she bestows upon the 43rd president. She mentions Giorgos Rigas “whose populous scenes of life in the Greek mountain village of his childhood are every bit as good as Grandma Moses’ work.” How would she rank Bush against Grandma Moses? What makes one “outsider” artist good enough for a show and the other the butt of Internet jokes? Bush, of course, never asked to be featured in any art fair, providing the most obvious answer for why he is not showing alongside Rigas and other outsider painters.

Clearly we judge art by the artist; we ridicule Bush not because of the awkwardness (though there’s plenty of that), but because of who he is. Responding to another commenter, Saltz admits that “It DOES count a lot that they were painted by who they are painted by. I would like them if they were painted by Karl Rove too. Or anyone. But not quite as much maybe.”

Gallerist Jack Fisher makes a similar point, drawing the inevitable Hitler comparison, though the Huffington Post notes that he “only compar[es] the two artistically, not historically” — a point lost on the right-wingers who immediately started wailing about liberals likening the former president to a Nazi. “There’s this peculiar sort of interest in a famous figure having painted,” Fisher says, and another critic concurs: “It’s one of those things where it’s only that it’s Bush that makes it interesting.”

That is to say, it’s impossible to look at art without thinking about the artist. Who can stand in front of a riotous, splatter-flecked Jackson Pollock painting without remembering the artist’s own emotional outbursts, his battles with alcohol and his violent death in a car crash? Does knowing about the artist add to or detract from a work? Perhaps one can appreciate a Renaissance Madonna or a Greek statue without knowing that Raphael or Phidias was behind it, but even Monet’s paintings are less impressive if one is ignorant about the painter’s fascination with light and intention to depict the world in purely visual terms. Modern art — think of Damien Hirst’s spot paintings, which to many viewers look like glorified wallpaper — is even more reliant on personality and the cachet of reputation. To say we are interested in Bush’s paintings because he is George W. Bush and not John Q. Public is to say nothing that is not true about any piece of contemporary art. It goes to the heart if the “what is art?” debate, which is eternal and certainly won’t be resolved in a blog post.

All the Freudian bizarreness actually bothers me less than the inevitable snark that laces some of the “reviews” of Bush’s paintings. Strangely, I’m actually more comfortable with the rude remarks about Bush’s possible guilt and general mental state — it’s nothing that hasn’t been said before about the president who couldn’t pronounce “nuclear” — than with the snotty bashing of his style, perhaps because I can put myself in his shoes. Would I want someone to write similar things about my lame attempts at oil painting or scrapbooking? How do you review a Sunday hobby? Your muffins aren’t good enough! Your ship in a bottle sucks! That’s pretty low.

I’m surprised here to find myself defending Bush. It’s one thing to psychoanalyze based on legitimate policy mistakes; Bush’s record is undeniably abysmal, and raking him over the coals via psychobabble seems par for the course. After all, the pundit class has already accused him of having daddy issues, of invading Iraq essentially to get back at the man who outplayed his papa. That’s a personal attack, sure, but it’s also at least tangentially related to something Bush did as president. (If you don’t want to be called a daddy’s boy, don’t use trumped-up evidence to invade the country your father attacked in 1991.) The Freudian analyses also seem harmless, in part, because they poke fun at the stuffy tropes of reviewers themselves. Far crueler are the nasty remarks about Bush’s talent and style, which Gawker calls “as awkward and simple as you’d hope” and a critic quoted by the Huffington Post labels “very pedestrian and clumsy.”The critique that put me off most of all was Amy Davidson’s reaction at the New Yorker:

That brings us back to Bush’s self-portraits, which have the unfortunate appearance of having been painted by numbers. According to The Smoking Gun, he had e-mailed them to his sister, so perhaps he was proud of them. Or maybe he never would have shown them to anybody else; this art, after all, was stolen . . . . The one in the shower shows his bare upper back; the one in the bath is a view of his legs and toes. Is he experimenting with perspective, or is his right knee just swollen? Captions or thought bubbles might help; there seems to be space for them, near the shaving mirror and the tap, respectively. But then what does one expect George Bush to say?

Actually, I’d take that first slam as a compliment. A child can paint by numbers, but to create free-hand a scene that looks as realistic as the landscape on the DIY box takes some skill. Davidson even admits that Bush never intended to show his paintings to the world. He never intended to open himself up to criticism; we’re seeing the art only because something he meant to keep private was instead maliciously exposed. It’s one thing to opine about the president’s psychological hang-ups and guilt complex — Maureen Dowd still does that every week, though she breaks from form by charitably calling Bush’s art “surprisingly interesting and humanizing” – but trashing his lack of talent just because you can has nothing to do with his actions. These naysayers, who probably can’t tell one end of a paint brush from the other themselves, treat a lack of artistic genius as some sort of personal failing, not just a political one. They deliver mean-spirited low blows better suited to blogs like Daily Kos than the New Yorker.

The dangers of political writers who know nothing about art weighing in on Bush’s level of talent is perfectly encapsulated by Dowd’s attempt to parse the paintings’ artistic merit. She too references paint by numbers, but in a nicer context, writing that “The president who came across as a paint-by-numbers executive in public life can actually paint in private life.” But then her criticism goes off the rails:

It’s weird because W.’s presidency was not a reality-based undertaking; it did not look carefully at the world. And yet his paintings reflect meticulous optical observation.

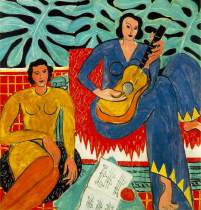

What’s really weird is that Dowd has it exactly backwards. The paintings don’t reflect meticulous optical observation at all. The perspective is off; likely, this is because perspective is something really, really hard for an amateur artist to get right, though Cezanne and Picasso pretty much killed off the notion that classical Western perspective is the only legitimate way to depict the world. (Look at Matisse’s portraits and interior scenes — their unreality and lack of perspective is intentional; a feature, not a bug.) The flatness and skewed angles of Bush’s work is common among self-taught artists, and brings to mind the contrast between “professional” portraits of George Washington and the folk art of the same period. Dowd’s backward definition of “meticulous observation” is refuted by this description of Bush’s paintings from an actual art critic in the Guardian:

Presumably the word critics would use is “naive”. Look at that impossible reflection in the shower mirror, for starters, or the perspective on the bathtub, which must be the longest and narrowest in existence.

At least Dowd doesn’t join Davidson in looking down her nose at the former president’s skill level. Snark about actual artists all you want, but attacking a layperson, especially someone brave enough to try something new, is classless. Instead of hunkering down at his ranch and shooting quail or clearing brush, Bush is expanding his horizons. Surely those who savaged the president for being a parochial anti-intellectual who displayed a shameful lack of curiosity about the world beyond Texas should applaud his ventures, even if they’re confined to his bathroom. (Would his critics be happier if he set up his easel alongside the socialists smoking in Paris cafes?) Snipping about quality strikes me as particularly tacky, considering Bush never intended anyone to critique his paintings.

The Huffington Post writes that the art experts it contacted “were perplexed by the images.” What is perplexing about a beginning painter, a Sunday dabbler, not producing Picasso-level work? HuffPo smugly maintains the pretense that the paintings should be good, when there is no reason they should be. Why should a man be mocked for a private hobby? I write terrible poetry that I would never want the country to read. If someone hacked my Yahoo account and it leaked out, what right would people have to criticize it? It’s like bashing someone’s diary for bad prose. Bush is not putting himself out there, bragging that he’s a great artist or, like other celebrities, assuming he’s talented enough for a gallery show. Unfortunately, in the age of omnipresent paparazzi and reality TV, we think we have a right to an opinion about everyone’s lives, just because the Kardashians have provided us with a slice of theirs. It’s one thing for non-artists to stand in the Gasogian and rip an installation piece to shreds; after all, the artist is putting himself up for ridicule. But Bush is no more a self-proclaimed artist than Amy Davidson or any of the people quoted by the Huffington Post. He has never claimed to be anything but someone who paints to fill the time. Bush made enough errors in office to criticize him for the next 50 years. Why declare open season on his hobby?

In place of these sharp-tongued responses, I’d rather read a sympathetic interpretation of Bush’s work, like this one from the Guardian, which touches on our own voyeuristic interest in the art:

There’s always something disorienting about those moments when you’re suddenly reminded that presidents, ex-presidents, prime ministers and others are people, with inner lives and vantage points, who take showers and stare at their feet in the bath. This jolting realisation is all the greater when the leader in question is Bush. We spent years, after all, trying to fathom what was going on in there: nothing much at all? Terrifying messianism? Criminal incuriosity? All manner of Oedipal hang-ups? Pictures of Bush in the bathroom don’t answer that, of course. But like any self-portrait, they inch us towards empathy. They invite us to imagine that being inside Bush’s head is something it’s possible to imagine.

And that’s the real point of all art, isn’t it? To ask us to imagine.